The rarest of comebacks

And possibly the next member of an odd club

In today’s This Again:

A defeated ex-president wins reelection.

The secret ballot changes America.

Theodore Roosevelt gets a role model.

He vowed to drain the swamp. He towered above his party and the Congress with his words and deeds. The New Yorker fought for the little guy. He was anti-corruption and incorruptible. Because he was outside the political class, he could not be bought.

Physically, he was almost 300 pounds. His wife was 30 years his younger. He liked jokes.

He distrusted the news media. It was their fault he was ridiculed, their fault his winning streak was questioned, and their fault he had to overcome a sex scandal to become the first Democratic president since the Civil War.

Grover Cleveland did not plan to be the first and only president to serve non-consecutive terms, something Donald Trump would repeat with a victory next month.

Cleveland’s similarities with Trump are an unfair comparison. Cleveland was never impeached. He was never charged with state or federal crimes. He was never found guilty in a civil trial. Amid a storm at the Capitol, Cleveland held the umbrella for his Republican successor.

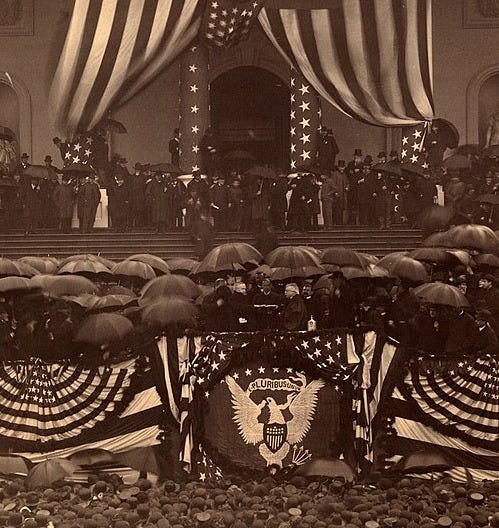

Eight years later, he became the first president recorded on film as his second Republican successor took his Oath of Office.

The Veto Mayor, Grover the Good

Three years before the Executive Mansion (as it was then known), “Grover the good” had been Mayor of Buffalo, New York. He was nominated for governor as a compromise candidate who could appeal to reform-minded voters.

He benefited from a fractured opposition. He was nominated for governor because Democratic bosses could not agree on anyone else. In the election, Republicans split themselves in two. One half favored traditional government appointments, the spoils system, and the other wanted to see more civil service reform. Cleveland, a reformer, could appeal to Republicans who soured on self-dealing politicians and party machinery that had nurtured, sometimes violently, railroads, industry, and bi-racial coalitions in the South after the Civil War.

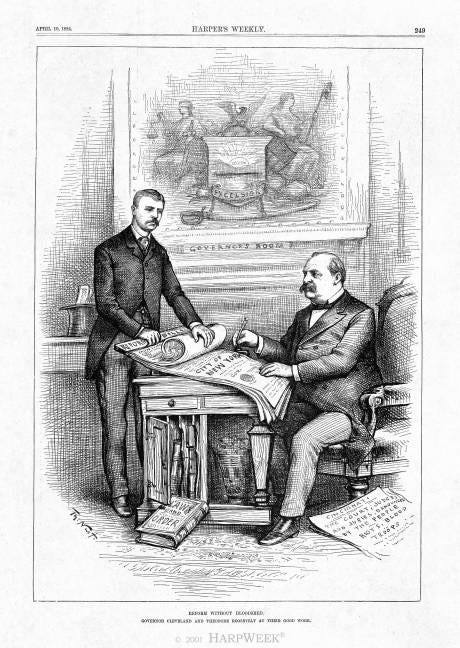

He was a bipartisan governor too. In frequent collaboration with Theodore Roosevelt, then a state Assemblyman, Cleveland signed laws that weakened the Tammany Hall machine in New York City.

The dynamics that powered his ascent repeated in the 1884 presidential election. He would be the compromise candidate for Democrats. Opposition Republicans would, again, divide and weaken themselves.

Like the 2016 election, there were dozens of variables could have changed the outcome. Cleveland’s popular vote majority was 0.5%. New York was the biggest swing state and prize, and Cleveland carried his home state by 1,200 votes out of the more than one million cast.

The Veto Mayor would shrink government. He vetoed pension plans for Union Army veterans. He vetoed emergency rescue and aid for Texas farmers obliterated by drought. “Though the people support the Government the Government should not support the people,” said his veto message.

His vetoes were either his stubborn honesty or a small town mayor’s idea of principled frugality. Either way, he was able to mix anti-corruption with pro-business policy—something both parties have repeated ever since.

Four years later, he lost as he won—in a squeaker. Republican robber barons spent lavishly to bring New York City bosses and machines against Cleveland. Corruption was more overt in Indiana, the second pivotal swing state. There, state Republicans organized and paid undecided voters.

Facing reelection, Cleveland again won the popular vote, but lost the Electoral College.1

Back in power, Republicans undid many of Cleveland’s popular works. Taxes were raised and, for the first time, Congress spent $1 billion. The sticker shock decimated Republicans in the midterm elections.

After that, Cleveland began to do things he’d rarely done in his first two national elections: He campaigned. He promoted his record. He described what he would do with power and he helped make famous a new and fragile ballot concept imported from Australia.

Ballot reform and Cleveland’s return

In New South Wales, the Australian territory, the government made official election documents. Voters got them, one-by-one, at official polling places. Ballots were identical, so choice and preference were visually unknowable. It was all opposite of American election norms and laws that had no standard ballot.2 Secret ballots marked the end of widespread voter fraud that could determine election outcomes.

In 1888, when Cleveland was defeated, these secret ballots existed in Lexington, Kentucky and Massachusetts. Nine states joined them the next year (including Indiana). When Cleveland stood for his third campaign, citizens in 38 of the 45 states voted by secret ballot. (Southern states held out the longest.)

Ever the reformer, Cleveland advocated for the revolutionary secret ballot.

Historians rank Cleveland in the middle or above average presidents. To the extent he’s remembered, it’s because of the non-consecutive terms.

Cleveland arguably revived and enhanced the executive branch after 12 years of Republican trickle-down economics, bailouts, and handouts. I would argue he’s best remembered as a template for the future and consequential New York presidents.

New Yorker Theodore Roosevelt is generally considered to be the first “modern” president, but he built on his Cleveland’s record and vigor. In a eulogy, Roosevelt called him a “happy warrior” who served honorably and understood “public trust” was essential.

The next New York president, Franklin Roosevelt, would copy his distant cousin’s path to power.

What about that other famous New York president? Trump was elected from New York, sure, but he was defeated as a Florida man.3 Unlike the New Yorkers, he’s ranked among the worst presidents. Cleveland won three popular votes. Trump lost two and, next month, might be his third.

Remember the choice: Talk with friends in swing states.

Popular vote winners lost five times in 235 years: in 1824, 1876, 1888, and 2000 and 2016. I predict 2024 will join that club if Trump wins next month .

With ballots standardized, parties found new targets that persist today: Voter registration and access.

And, as is his custom, he tested the limits of the law.